One of the best things about having a Substack that is not trying to make any money is that I can write about whatever the hell I want. There’s a freedom in that.

In the modern world, we seem to live our lives in boxes that are growing ever and ever smaller. For instance, in my day job, I am an oil and gas lawyer. (Yes, with all the associated cognitive dissonance that comes with also believing in the human impact on climate change.)

Maybe I am on Substack because I don’t want that to be all that I am. I am also someone who is interested in philosophy and neuroscience and quantum mechanics (at least the bits I can understand from Brian Cox and Neil de Grasse Tyson reels). In trying to make sense of a world that seems to be veering off-kilter in myriad different ways. In hoping to figure out the small part I might be able to play in making things better.

It could also be four years of living and working in Nigeria, where I have found my worldviews to be challenged and shaped in a fashion that I never would have expected when I accepted the job here. I remember, perhaps somewhat naively, telling my interview panel that I expected it to be hard, but that was the best part, because that was where real learning would happen.

It has been hard. Really freaking hard at times. Nigeria is a pressure cooker. A contrast in extremes and broken systems. Even from my privileged vantage point in a gated compound surrounded by barbed wire and armed guards. The socio-economic system is collapsing here to the point where the color of my skin makes me a target in the booming kidnap for ransom business here. As a result, most of my experience of Nigeria has been from behind the heavily tinted windows of my SUV, on my way from our compound to the security-approved “green zone” largely inhabited by other expats or rich Nigerians.

I leave the compound exactly once a week, for my spa day that has become my Saturday self-care ritual. It is ridiculously cheap. Five hours of services, including a “four hands” massage, is less than $100 (helped by the naira’s precipitous decline). I follow it with a stop at the ridiculously expensive expat grocery store, where my purchases can easily double my driver’s monthly salary. And we pay really well for domestic staff (I can also feel myself cringe internally, just saying the phrase “domestic staff”).

In 2024, the president of Nigeria, Bola Tinubu, increased the national minimum wage from 30,000 naira a month to 70,000. At current black market rates, that means the minimum wage increased from about $19 a month to about $44 a month. We pay our staff several times that (a salary in excess of what an entry-level engineer might expect to earn) and it still feels exploitative. We have a full-time stewardess, who does all of our cooking and cleaning and generally making sure the house runs smoothly. We also have a full-time driver who does all of our shopping for us (except for the specialty items from my Saturday runs), so we don’t have to brave the insanity of Lagos traffic. In the US, the same amount let us afford to have a cleaning service come to our house twice a month.

A privileged life, lived behind cement walls.

Until May of last year, we also had a part-time cook, Lily. We were on vacation in Paris when we received a frantic WhatsApp call at 3AM from our stewardess, telling us that Lily had collapsed and died. She was 38. She hadn’t been feeling well but didn’t tell anyone. She came to work, ignored the pain in her chest, and died of a heart attack in the communal bathroom of the domestic quarters on our compound.

Pressure cooker. Health care here is a luxury out of reach of most.

I understand that, although not to the degree of the lived experience of most Nigerians. I grew up the only child of a single teenage mother. Health care for us was also a luxury. You only went to the doctor if you thought you might be dying. When I first got medical insurance after I graduated from law school, I went to the dentist for the first time in over five years. My reward was 12 cavities that needed to be filled.

But when we needed it, medical care was available, even if only at the urgent care centers my mom referred to a “doc in the box.” Lily was not so fortunate.

This year, our stewardess, Laraba, started showing up to work with a tightness around the eyes and a slow gait that spoke of tremendous pain. We weren’t going to let the same thing happen to her that happened to Lily. We found out she has polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) and paid for treatment that we thought was coming from an actual medical professional. Only to find out she was getting shots of who knows what from a “nurse” that worked out of her home.

About a month ago, Laraba collapsed on the stairs. We rushed her to the hospital, where she was admitted for a few days. At the time, we were getting information from her, instead of directly from the doctors. As a result, it wasn’t until a week after she was discharged that she admitted that the doctors had said she needed surgery.

She didn’t want to do it. I don’t blame her. Surgery in any case is scary, but in Nigeria the fear seeps into your pores and clings to your bones. Am I seeing a qualified doctor? Do they know what they are doing? Are they going to take care of me or make me worse? Nigeria has the third highest rate of infant mortality and the second highest rate of maternal mortality in the world. Many people opt out of the healthcare system entirely, electing for prayer houses over hospitals. Every year, droves of qualified medical professional japa, leaving Nigeria for greener pastures.

By the time Laraba finally agreed to surgery and let us bring her back to the hospital, blood flow was being cut off to her ovaries, one cyst had ruptured and the other was septic. If she hadn’t let us convince her to go in, and if we hadn’t been willing to pay for her treatment, she likely would have died.

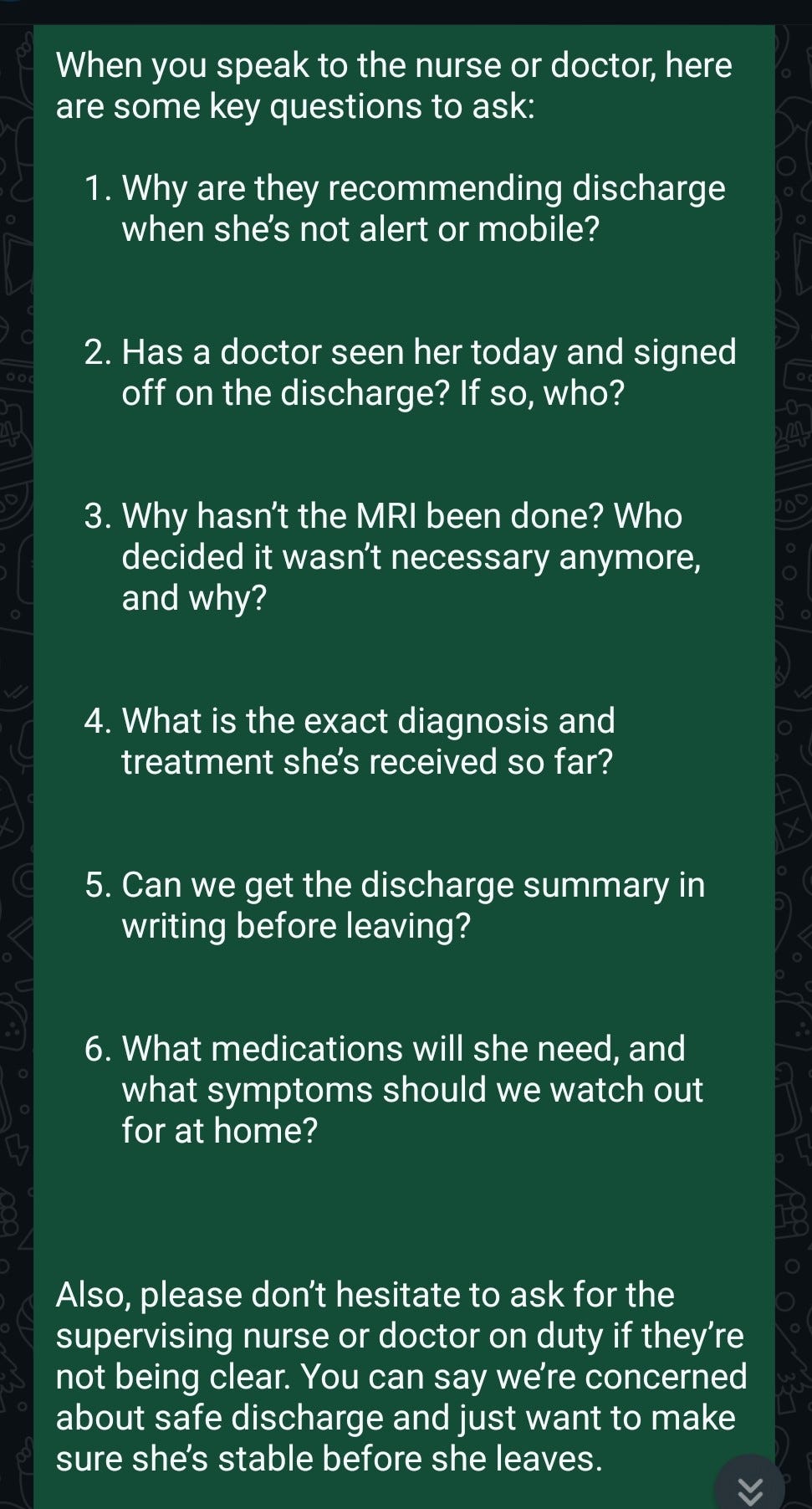

Through it all, I was frantically using AI to understand Laraba’s symptoms and the (often garbled) information that Laraba’s sister, Zaynab, shared. There is no trust in the system. I had to make sure she was getting the right treatment, the right diagnosis. I crafted lists of questions for Zaynab to ask the doctor, sending them via WhatsApp. At this point Laraba was so consumed with pain she was barely coherent.

It shouldn’t be the case, but I am certain she got better treatment because white people with money were at the nurse’s desk, asking why they were planning to release Laraba when they hadn’t ruled out ovarian torsion. It wasn’t long before Zaynab just started putting the doctors directly on the phone with us.

What haunts me still is the nearly unbearable weight of responsibility Laraba and Zaynab surrendered to us. Laraba was completely out of it from pain, and Zaynab just seemed … lost. When I tried explaining the severity of her condition, I watched confusion cloud their eyes, followed by a nod of deference that said, “Please, just tell us what to do.”

This was desperate faith. They couldn't evaluate our advice against alternatives, couldn't challenge our interpretations. They simply believed. And in a healthcare system where patients routinely die from treatable conditions, where doctors might see them for mere minutes between dozens of other cases, we became their primary medical authority. They didn’t trust the doctors, but they trusted us.

The price tag on Laraba's life: 9 million naira, or $6,000. In a country where minimum wage workers earn 70,000 naira monthly (assuming their employers actually comply with the minimum wage requirements), this represents nearly 11 years of their entire income. Not disposable income. Every single naira earned, without food, without shelter, without transportation. Her survival cost more than a decade of someone's complete existence. In Nigeria, this financial chasm separates those who live from those who die.

It’s the rainy season in Lagos. On the main road between our compound and Victoria Island, the constant erosion from daily rains has turned the right side of the Lekki Expressway into a riverbed. As Laozi notes in the Tao Te Ching, “Nothing in the world is as soft and yielding as water. Yet for dissolving the hard and inflexible, nothing can surpass it.”

Intrepid drivers in SUVs, semi-trucks older than me, and the ubiquitous white minivans that serve as public transportation here, make their way slowly over the hills and valleys carved by the endless rains. The furrows grow deeper with their passage.

The rest of us move over to the left, where the asphalt remains largely intact. Traffic slows to a crawl. I am practicing mindfulness and my time in the car is spent in observation of the world outside my tinted windows. Some days, like today, my mind is scattered and the only thing I can focus on is how many people I see urinating on the side of the road. I count them instead of counting my breaths. I am up to four.

I am on my way to pick up my husband from the hospital. While Laraba was still recovering from her surgery, my husband, Wolf, finally asked the doctor on our compound about the weird lump behind his right knee. That was on Monday. On Tuesday, he had an ultrasound, where they diagnosed it as an aneurysm. On Wednesday, he had a CT scan, which found another aneurysm behind his left knee, along with a second smaller one in his right knee. On Thursday, we frantically packed a go bag and headed to the hospital, thinking Wolf would be having surgery. Only to have the surgeon, Dr. Hammed, say, “Oh, I am not operating on you today. You’ll have to come back tomorrow.”

Normally, my company’s medical team would never authorize having surgery here. The expectation is that you would go back to the US for anything serious. But one of Wolf’s aneurysms has a clot and he cannot get on a plane. We have no choice. Dr. Hammed had (not so) subtly dropped into our conversation that he worked part of the year in Florida. I let that reassure me.

Dr. Hammed had said Wolf’s surgery was going to be at 4PM on Friday, but at 11AM, our clinic doctor started texting us to tell us we need to be there by noon. So off we went. There were no pre-op instructions. Wolf ended up having to shave a very sensitive area with a disposable razor and no shaving cream in a bathroom with a lock that didn’t work. Some elderly Nigerian woman got to see my husband in his full glory. The favor was returned when my husband went out the other door, only to see a different elderly Nigerian woman in her full glory, also getting prepped for surgery.

And then I waited.

In all the chaos, I had forgotten to arrange for an armed security escort from the hospital. By the time Wolf was out of surgery, I only had an hour and a half to spend with him if I wanted to make it back by curfew. He was mostly out of it, but Dr. Hammed assured me the surgery went well, that he was able to successfully coil off the aneurysms, to access the outflow and the inflow, so that he didn’t have to put coils in the aneurysm itself. I wanted to believe him but didn’t know if I should. What choice did I have? I peppered Wolf’s face with kisses and walked out, feeling guilty as hell that I would be sleeping in our own bed while he was stuck in a cramped ward.

In the car, I try to stop my mind from spiraling around thoughts of whether the surgeon was too overconfident. Our cell service is sketchy at best here and I haven’t heard anything from Wolf since I left the clinic. In Nigeria, a lot can happen in 14 hours.

We were supposed to be on a plane to Portugal, so I could present my paper to the International Sustainability Transitions conference. The best laid plans. I feel small, like a mouse.

I try to label my thoughts as thinking. I’m also supposed to label feelings as feelings but I am too numb for that. Instead, I add another guy taking a leak to my tally. My driver braves the right side of the road to get around a stalled vehicle, and I focus on the feel of our SUV seeking traction, rising and falling in slow motion. It reminds me of our safari jeep rides in Kenya. Thinking, I remind myself.

Finally, we are there.

I brace myself as I walk up the stairs to the post-op ward. I don’t know what to expect. What I find is my husband sitting in a chair, playing on his phone. He’s wearing his hospital gown still, but they didn’t have slippers that would fit his size 13 feet, so he has on his shoes. He tells me he also has on underwear, like it’s a secret, because he wasn’t going to let them tell him he could put any on. I want to cry in relief, but I don’t. I used to be quite good at crying, but somewhere along the way I lost that skill.

For some reason, it’s only when I arrive that he realizes he could have asked for the WiFi password. Then again, they did give him the good drugs.

We had been told yesterday that he likely wouldn’t be discharged until noon, so I thought we had a couple of hours of waiting. Wolf’s phone, finally connected to the world, starts dinging incessantly as all of the alerts start rolling in. For once, I don’t mind (mostly). I understand the desire for a distraction, and after all, I did have internet all night long.

After less than a half an hour, the nurse comes by, seeming to be in a hurry to release Wolf early. I think they need the bed for someone else, but neither of us is going to complain. It is a rare gift to have something take less time than expected here.

A few minutes later, Dr. Hammed comes by for the discharge. He seems surprised by the fact that Wolf had a lot of pain in his calves. Why was he surprised? Shouldn’t he know what the after-effects would be? Is it something we should be worried about? All questions I could have asked but didn’t, because we just wanted to GTFO.

It’s been two weeks since Wolf’s surgery, so we make our way back to hospital for his post-surgical follow-up. Happy Fourth of July.

Wolf mentions that the severe pain he had for the first ten days or so has finally subsided. Dr. Hammed again seems surprised. Again, I wonder, did he not know what would happen? Then again, my husband, always a special, special snowflake, had an extremely rare kind of aneurysm, saccular instead of fusiform. I know this because I did my own research, given the paucity of information we got before Wolf’s surgery.

I’m pretty sure this surgery was a feather in Dr. Hammed’s cap. The TVs in the waiting room of the hospital are a running loop of videos bragging that this procedure or that was the first performed in Nigeria. I wonder if Wolf will soon feature in one of these videos.

Dr. Hammed casually tells us that he normally wouldn’t have operated on both aneurysms on the same day. He would have done one leg and then had Wolf come back for the other leg in a week. In Nigeria, he says, you have to factor in cost. All of the supplies have to be imported from the US, so by doing both legs on the same day, the only additional materials he had to use were the coils for the other leg.

According to Gemini, doing both surgeries at once likely increased Wolf’s “immediate perioperative risks compared to staging the procedures.” I’m just glad we didn’t have to go through this twice.

It’s time for the follow-up ultrasound, to see how the coils have worked, if the aneurysms are fully clotted off, or thrombosed. Dr. Hammed starts quizzing one of the nurses on whether he has read the patient history. He has not and starts stammering out excuses. I feel uncomfortable, not sure where to look as Dr. Hammed chastises him.

Wolf climbs onto his belly on a table meant for gynecology exams. Dr. Hammed apologizes for the stirrups and tells Wolf to ignore them. He shows us the ultrasound screen and we nod as if we understand what we are seeing when he points out, “See, there are the coils. And there’s where the aneurysms were.”

Dr. Hammed seems to be in a hurry to get to his next appointment. For a country where time is supposed to be more fluid, there is always this underlying sense of urgency. A frenzied inertia. Festina lente.

Now that Wolf’s been cleared to fly, we’ll be headed back to the US so we can get second opinions on, well, everything. The trips back home are always my least favorite, because they always feel more like work than vacation.

What I've learned in Nigeria isn't what I expected when I sat before that interview panel. I thought I'd learn about resilience and adaptation. Instead, I've learned that systems fracture along lines of privilege, creating parallel realities where the same city holds both life-saving treatment and preventable death, separated only by naira notes and the accident of birth.

When people ask what Nigeria is like, I struggle to answer. Do I describe the incredible warmth of people like Laraba and Zaynab? The absurdity of counting roadside urinators to practice mindfulness? The gut-wrenching reality that the price of a life can be calculated in years of minimum wage labor?

Perhaps what I'm really writing about is the cognitive dissonance of it all. Working in oil and gas while believing in climate change. Living behind walls while trying to understand what's beyond them. Being simultaneously a potential savior and part of the problem.

I don't have neat conclusions to offer. Just questions that have followed me from those cement walls to this keyboard. Questions about responsibility, about what we owe each other, about how to live ethically in a world of such stark contrasts.

As I prepare to return to the US for those second opinions, I carry these questions with me. They've become part of who I am now. Complications without easy resolutions, much like Nigeria itself.

Alyssa, this is such an amazing post! So many feelings come to the surface, the juxtaposition of living in Nigeria as an expat in a position of extreme privilege compared to the Nigerian citizens working their fingers to the bone just trying to survive. You are a truly gifted writer.

Beautiful writing and so descript of Nigeria. I'm so glad Wolf has an all clear and I hope you get to enjoy some of the trip to america!